Probiotics and Irritable Bowel Syndrome: The Definitive Science-Based Guide to Finding Relief

Suffering from Irritable Bowel Syndrome? We dive deep into multiple meta-analyses covering over 9,000 patients to reveal which probiotics truly work, for which symptoms, at what dosage, and what co-adjuvant treatments like the low-FODMAP diet can transform your gut health.

IRRITABLE BOWEL SYNDROME

Nuri El azem De haro

10/3/20257 min read

Probiotics and Irritable Bowel Syndrome: The Definitive Science-Based Guide to Finding Relief

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) is much more than just a simple "stomach ache." It's a complex, chronic gastrointestinal disorder affecting between 5% and 10% of the world's population, with a higher prevalence in women [5]. It's characterized by a set of debilitating symptoms: recurrent abdominal pain, bloating, gas, and a persistent alteration of bowel habits, whether as diarrhea (IBS-D), constipation (IBS-C), or a mix of both (IBS-M) [1, 5]. In addition to physical discomfort, IBS imposes a substantial economic and social burden, severely impacting the quality of life and productivity of those who suffer from it [3, 6].

For a long time, treatments focused on alleviating symptoms in isolation. However, a growing body of scientific evidence has shifted the focus toward a complex and fascinating ecosystem: the gut microbiota. The idea that an imbalance in our gut bacteria is a central piece of the IBS puzzle has gained immense traction [3]. This leads us to a crucial question: Can probiotics, the "beneficial living microorganisms," be the key to real and sustained relief?

To answer this question, we have deeply analyzed six large-scale systematic reviews and meta-analyses, which collectively evaluate data from dozens of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and thousands of patients. This is the verdict of science.

The Origin of the Problem: What Causes Irritable Bowel Syndrome?

IBS is understood today as a disorder of the gut-brain interaction [3, 6]. It's not an imaginary disease; it's a real condition with complex pathophysiological bases. The main scientific theories point to:

Gut Dysbiosis: This is the alteration of the gut microbiota balance. IBS patients often show less diversity of microorganisms and a reduction in key beneficial bacteria, such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, while potentially pro-inflammatory families like Enterobacteriaceae increase [1, 5].

Low-Grade Inflammation and Gut Permeability: An increase in the permeability of the intestinal barrier (the so-called "leaky gut") has been observed in IBS patients. This allows certain substances to pass into the bloodstream, activating the mucosal immune system and generating mild but chronic inflammation that contributes to symptoms [1, 5].

Visceral Hypersensitivity: The nerves in the gut of people with IBS are hypersensitive. This means they overreact to normal stimuli, such as gas distension or bowel movements, interpreting them as intense pain [1, 5].

Altered Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs): These compounds (acetate, propionate, and butyrate) are produced by the microbiota when fermenting fiber and are vital for colon health. Studies show an altered SCFA profile in IBS patients, highlighting a significant increase in propionate and a reduction in the proportion of acetate, which could serve as a disease biomarker [7].

Given that the microbiota is involved in all these processes, modulating its composition and activity through probiotics presents itself as a direct and promising therapeutic strategy [3].

The Scientific Evidence: What Do the Large Studies Tell Us?

To evaluate the efficacy of probiotics, we cannot rely on a single study. The strongest evidence comes from meta-analyses, which are statistical studies that combine the results of multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The articles analyzed for this guide compile data from up to 81 RCTs and over 9,200 participants, offering a very robust perspective [3, 6].

The overwhelming consensus of these analyses is clear: probiotics, as a general category, are significantly more effective than placebo for improving global IBS symptoms, abdominal pain, and the quality of life for patients [1, 4, 5, 6]. A three-level meta-analysis, an advanced statistical method, estimated that probiotics have a medium-to-large effect size on the improvement of these symptoms [6].

The Key is in the Strain: Probiotic Guide for Each Symptom

The most important question is not if probiotics work, but which ones work and for what. Thanks to network meta-analyses, which compare multiple treatments simultaneously, we can classify the efficacy of specific strains and blends for each symptom.

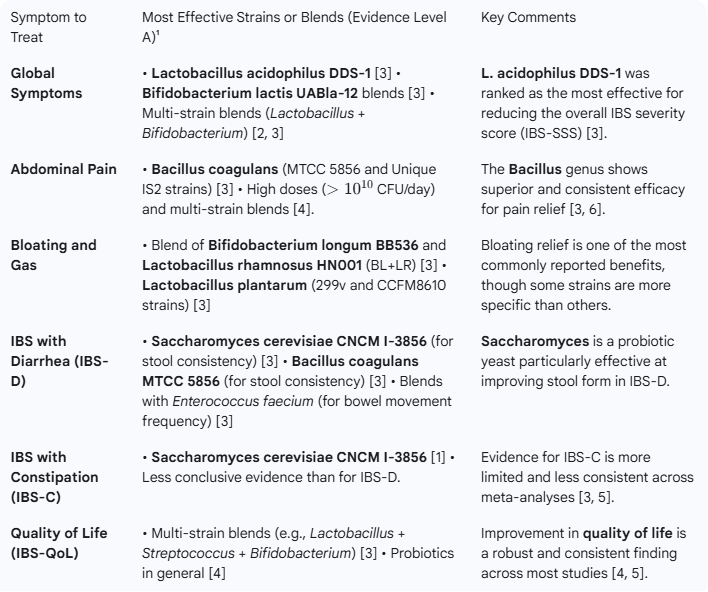

Probiotic Efficacy Table for IBS (Based on Network Meta-Analyses)

¹ Evidence Level A refers to probiotics that are not only superior to placebo, but also to other probiotics with demonstrated efficacy [3].

The information contained in this table is crucial. According to the issue presented in each patient, we can choose the most suitable probiotic strain to treat their symptoms. Therefore, if you are looking for a product that fits your needs, here is a direct link to Amazon’s webpage.

Dosage and Duration: How Much and For How Long?

Dosage: Most studies support a minimum dosage of 109 CFU (one billion colony-forming units) per day to observe effects [1]. For more specific symptoms like abdominal pain, higher doses, above 1010 CFU/day, seem to offer greater benefit [4].

Duration: The beneficial effects of probiotics can begin to be noticed within 4 weeks of continuous treatment [1]. Interestingly, a large-scale meta-analysis observed that shorter-duration treatments (less than 4 weeks) were associated with a greater effect size, while effects tended to diminish in longer studies [6]. This doesn't invalidate long-term treatments, but suggests that the initial benefit may be the most pronounced, possibly due to a strong placebo effect in the first few weeks or the inclusion of patients with more severe symptoms in longer studies [6].

Co-adjuvant Treatments: Boosting Results

Taking probiotics is only one part of the strategy. For a comprehensive management of IBS, it's essential to consider other approaches that act in synergy.

The Low-FODMAP Diet: The Star Co-adjuvant

The low-FODMAP diet (Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, and Polyols) is one of the dietary interventions with the strongest scientific support for IBS [2]. These short-chain carbohydrates are poorly absorbed in the small intestine and rapidly fermented by bacteria, producing gas and drawing water, which causes bloating, pain, and diarrhea [7].

Efficacy: Meta-analyses confirm that a low-FODMAP diet is highly effective at improving global symptoms and reducing IBS severity [2, 7].

Synergy with Probiotics: The combination of a low-FODMAP diet along with probiotic supplementation has proven to be the most effective strategy of all for IBS symptom relief in some studies [2]. While the diet reduces the "fuel" for gas-producing bacteria, probiotics help restore a healthier balance.

Effect on SCFAs: A low-FODMAP diet has been shown to significantly reduce the fecal concentrations of propionate, which is elevated in IBS patients, helping to normalize the profile of intestinal metabolites [7].

Other Interventions: Prebiotics, Synbiotics, and Fecal Transplant

Prebiotics and Synbiotics: Unlike probiotics, the current evidence on prebiotics (fiber that feeds good bacteria) and synbiotics (a combination of prebiotics and probiotics) is weak and inconsistent. Meta-analyses have not found a significant benefit of these interventions over placebo for IBS [1, 5].

Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT): This procedure involves transferring the microbiota from a healthy donor to the patient's intestine. Network meta-analysis shows that FMT is an effective therapeutic option, with effectiveness comparable to that of probiotics [5]. Although it is more invasive, it represents a promising alternative, especially for more resistant cases.

A Critical Look: Strengths, Weaknesses, and Common Ground

Common Strengths:

Consensus on Efficacy: All meta-analyses conclude that probiotics are superior to placebo.

Safety: Probiotics are extremely safe. The number of adverse events is not significantly different from the placebo group [1, 4, 5].

Personalization: The evidence points to a future of personalized treatment, selecting specific strains for each patient's predominant symptoms [3].

Weaknesses and Challenges:

Heterogeneity: This is the main "weak point." The analyzed studies are very different from each other (strains, doses, duration, populations), which makes it difficult to draw definitive conclusions for a single formulation [3, 6].

Lack of Direct Comparisons: Most trials compare a probiotic to a placebo, not to each other. More "head-to-head" studies are needed [3].

Long-Term Effects: Most studies are short-term. More research is needed on the sustainability of benefits and the necessity of continuous treatment [6].

Practical Conclusions: Your Roadmap for Managing IBS

Probiotics are a Valid and Effective Therapy: They are not a miracle cure, but they are a therapeutic tool with solid scientific backing for IBS [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6].

Identify Your Dominant Symptom to Choose the Strain: Not all probiotics work for everything. Use the table in this article as an initial guide to look for products containing the most studied strains for your main problem (pain, bloating, diarrhea) [3].

Verify the Dosage: Look for products that guarantee a dosage of at least 109 CFU/day [1].

Combine with the Low-FODMAP Diet: This combination has proven to be the most potent strategy. Consider working with a registered dietitian to implement this diet correctly, as it is restrictive and must be supervised [2, 7].

Be Consistent and Patient: Give the treatment a minimum of 4 weeks to evaluate its effectiveness [1]. Changes in the microbiota and symptomatic response are not immediate.

Always Consult a Health Professional: This article is informative but does not replace medical advice. Talk to your doctor or gastroenterologist before starting any new treatment to ensure it is the right option for you.

In summary, science tells us that modulating our gut microbiota is one of the most effective strategies we have for managing Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Probiotics, intelligently selected and combined with dietary approaches like the low-FODMAP diet, offer real and tangible hope for recovering the quality of life that this condition often takes away.

Bibliography

[1] Zhang, W. X., Shi, L. B., Zhou, M. S., Wu, J., & Shi, H. Y. (2023). Efficacy of probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics in irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Journal of Medical Microbiology, 72(10), 001758.

[2] Lei, Y., Sun, X., Ruan, T., Lu, W., Deng, B., Zhou, R., & Mu, D. (2025). Effects of Probiotics and Diet Management in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Nutrition Reviews, 83(9), 1743–1756.

[3] Xie, P., Luo, M., Deng, X., Fan, J., & Xiong, L. (2023). Outcome-Specific Efficacy of Different Probiotic Strains and Mixtures in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 15(17), 3856.

[4] Yang, R., Jiang, J., Ouyang, J., Zhao, Y., & Xi, B. (2024). Efficacy and safety of probiotics in irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN, 60, 362-372.

[5] Wu, Y., Li, Y., Zheng, Q., & Li, L. (2024). The Efficacy of Probiotics, Prebiotics, Synbiotics, and Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 16(13), 2114.

[6] Chen, M., Yuan, L., Xie, C. R., Wang, X. Y., Feng, S. J., Xiao, X. Y., & Zheng, H. (2023). Probiotics for the management of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and three-level meta-analysis. International Journal of Surgery, 109(10), 3631–3647. [7] Ju, X., Jiang, Z., Ma, J., & Yang, D. (2024). Changes in Fecal Short-Chain Fatty Acids in IBS Patients and Effects of Different Interventions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 16(11), 1727.